The 50 greatest Handel recordings

Complete with the original Gramophone reviews of 50 of the finest Handel recordings available

All of these lists are, of course, subjective, but every recording here has received the approval of Gramophone‘s critics and are artistic and musical benchmarks. So if you want to hear Handel performance at its best, this list is the perfect place to start.

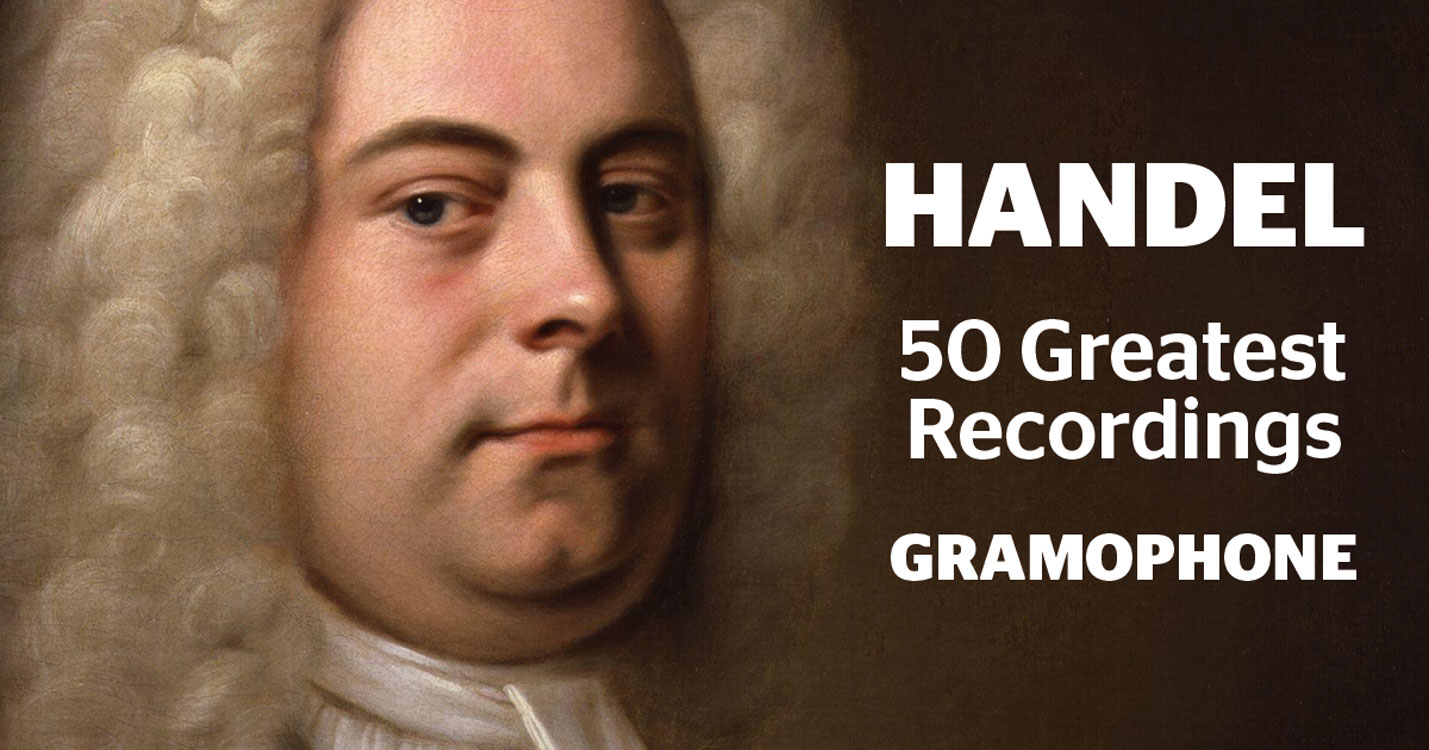

Organ Concertos, Op 7

Academy of Ancient Music / Richard Egarr hpd

(Harmonia Mundi)

Richard Egarr and the AAM have prepared their own performing edition of Handel’s Op 7 Organ Concertos, which has involved spontaneously creating ad libitum passages, or choosing other bits of Handel for the slow movements. The rich-sounding forces comprise 18 players, including oboes and bassoons; both their playing and Egarr’s solo contributions are of an impeccably high order.

Taking his cue from Charles Burney’s eyewitness accounts of Handel’s own performances, Egarr takes a bold, improvisatory approach to the concertos. The allegro movements are enlivened by rapid keyboard flourishes, liberal ornamentation (especially during repeats of whole sections) and delightful variants to the basic printed rhythms in the manner of French Baroque composers. Particularly startling is the opening bitonal chord cluster of the A major Concerto, Op 7 No 2; Egarr acknowledges his debt to the 17th/18th-century writer Roger North for this daring harmonic gesture. On a lighter note, listeners will enjoy all the cuckoo calls plus other birdsong motifs that crop up during the Cuckoo and the Nightingale Concerto in F.

Throughout the two CDs, tempi are beautifully judged, with a degree of flexibility and an avoidance of excessive speeds in the fast movements. In the three works for solo harpsichord, Egarr’s calm, measured pacing allows Handel’s music to flow clearly and effortlessly. The opportunity to hear the splendid Chaconne in G, HWV442, is highly rewarding; and, as Egarr points out, it uses the same bass-line and harmonic progression as the first eight bars of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

Egarr’s booklet-notes and a lovely collection of paintings featuring 18th-century London make for a booklet whose excellence matches that of the distinguished music-making. The recording is highly detailed – possibly a bit too close-up for some listeners. Full marks to Egarr for his choice of the 1998 Handel House Museum organ for the concertos; this modern British instrument is a copy of the type of chamber organ known to Handel. This is a superb set from all concerned.

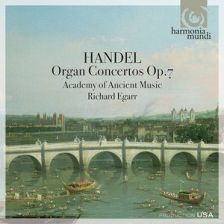

Concerti grossi, Op 3. Sonata a cinque, HWV288

Academy of Ancient Music / Richard Egarr

(Harmonia Mundi)

Richard Egarr suggests that Handel might have had more of a hand in the compilation of Op 3 than hitherto identified. Fresh speculation is a healthy opportunity to reconsider matters but the truly significant aspect of this recording is the new attention brought to Handel’s charming music. It is hard to think of a lovelier moment in all of Handel’s orchestral works than the spellbinding cellos interweaving under a plaintive solo oboe in the Largo of No 2. Likewise, the immense personality of the solo organ runs during the finale of No 6 is a potently precocious display of Handel’s genius at the keyboard. All such moments come across with vitality and passion.

The AAM has never committed Op 3 to disc before: under Egarr they sound as good as ever, perhaps even reinvigorated and a few degrees sparkier. These are for the most part lively performances full of fizzy finesse. There are several fine recordings that find a little more warmth, sentimentality and intimacy in the music, although the energetic brilliance so prominent in the AAM’s crisply athletic playing has its own rewards. The musicians are unanimously immersed in the intricacies of the music, but special mention must be made of violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk’s dazzling contribution to the dynamic finale of the ‘Sonata a cinque’ (a sort of violin concerto that Handel presumably composed for Corelli in Rome in about 1707).

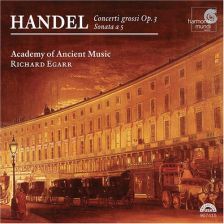

Concerti grossi, Op 6

Avison Ensemble / Pavlo Beznosiuk vn

(Linn Records)

The Newcastle-based Avison Ensemble, under the experienced direction of violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk, ranks alongside the best for musicianship, taste and style. It’s constituted on a smaller scale than Handel’s orchestra would have been, especially in its lower instruments; also there are no bassoons or lute in the continuo group, and only one harpsichord instead of Handel’s usual two. This is no different to other ‘historically informed’ recordings of Op 6 and need not be considered an obstacle to enjoyment. The optional oboe parts provided by Handel for a few of the concertos are omitted reasonably here.

Beznosiuk is an excellent judge of textures and tempi, and his leadership of the concertino group is authoritative and nuanced. Softly balanced cadences throughout the set are highly effective, and in fast music the interplay between concertino and ripienists is impeccable. The gutsier forthright music is played crisply and sweetly.

The music-making rarely veers towards becoming precious: phrases in the opening Largo of No 7 persistently taper off and diminish the lyrical pull of Handel’s writing, and, in the same concerto, the exclusion of harpsichord in favour of a barely audible organ seems odd considering the trouble Handel took over supplying detailed figured bass; the reduced vivacity also stifles the wittiness of the concluding Hornpipe. The concluding Gigue of No 9 is controlled and deliberate, where one might have hoped for swagger and panache. However, in the Tenth Concerto, the introspective melancholy of the Lento and the sudden mood-swings of the penultimate Allegro are impressive. No 11 has exuberance in its opening Andante larghetto, e staccato and its finale is thrillingly fleet-footed. The Avison Ensemble’s set may well remain rewarding long after the novelties of more precocious approaches have faded.

Water Music

Simon Standage, Elizabeth Wilcock vns The English Concert / Trevor Pinnock hpd

(Archiv)

It’s unlikely that George I ever witnessed performances that live up to this one. They are sparkling, tempi are well judged and there’s a truly majestic sweep to the opening F major French overture. That gets things off to a fine start but what follows is no less compelling, with some notably fine woodwind-playing.

In the D major music it’s the brass department that steals the show and here, horns and trumpets acquit themselves with distinction. Archiv has achieved a particularly satisfying sound in which all strands of the orchestral texture can be heard with clarity. In this suite the ceremonial atmosphere comes over particularly well, with resonant brass-playing complemented by crisply articulated oboes.

The G major pieces are quite different from those in the previous groups, being lighter in texture and more closely dance-orientated. They are among the most engaging in the Water Music and especially, perhaps, the two little ‘country dances’, the boisterous character of which Pinnock captures nicely.

Music for the Royal Fireworks. Concerti per due cori, HWV332-334

Ensemble Zefiro / Alfredo Bernardini

(Arcana)

The Italian ensemble Zefiro, directed by oboist Alfredo Bernardini, specialise in 18th-century music that gives prominence towards wind instruments. This lends itself to theMusic for the Royal Fireworks. Zefiro play the grand Overture with the perfect synthesis of splendour and dance-like charisma (too many versions possess too little of the latter). ‘La Réjouissance’ trips along lightly without a hint of clumsiness, but still has ample juicy magnificence. Theis zesty and fluid performance is a welcome change from stodgy readings in which everything is hammered home mercilessly. Zefiro bring a marvellous sense of light and shade to this music. Maybe Bernardini’s sparkling and communicative approach would have been too subtle for the great British outdoors in 1749 but it is curious that this beautifully engineered recording was made outside in the cloisters of a former Jesuit college in Sicily.

Zefiro also perform all three of the Concerti per due cori (1747-48) that Handel arranged for orchestra and two ‘choirs’ of woodwind and brass. These were intended as entr’actes in oratorio concerts, and it is fun to play ‘name that tune’. These shapely performances are phrased and paced to perfection, and exploit an enjoyable range of instrumental colours (whether oboe trios or bucolic horns, almost everything here feels right). This is one of the most enjoyable discs of Handel’s orchestral music in a long time.

Solo Sonatas, Op 1

Academy of Ancient Music (Rachel Brown fl/rec Frank de Bruine ob Pavlo Beznosiuk vn) / Richard Egarr hpd

(Harmonia Mundi)

John Walsh senior’s compilation of Handel’s sonatas for solo instrument and basso continuo (first printed c1730 and retrospectively known as Op 1) is a horrible mess from a scholarly perspective. Walsh cobbled together the collection, often printing sonatas for the wrong instrument, in the wrong key, or with some wrong movements; some sonatas are clearly not even composed by Handel. In his booklet essay, Richard Egarr does an entertaining job of conveying the confusing history and contents of ‘Op 1’.

Happily, there can be few qualms about the assured music-making. Rubato in slow movements sometimes disturbs the rhythmic pulse of Handel’s writing but otherwise the playing of the three principals of the Academy of Ancient Music sparkles, charms and soothes. Rachel Brown’s recorder-playing is sweetly elegiac in leisurely music, and subtle yet playful in quicker movements (the conclusion of HWV369); likewise, Brown’s flute-playing is gently conversational, and the unison opening of the Allegro in HWV363b is typical of the impressive understanding between Egarr and his soloists. Pavlo Beznosiuk’s contributions are by turns tender and refined. The violinist receives the four sonatas that were clearly not by Handel but plays them gracefully enough for issues of attribution to be temporarily forgotten. Frank de Bruine’s fluent oboe-playing is a particular delight. Egarr has dispensed with cello doubling the bass-line of the keyboard accompaniments; his harpsichord realisations give sensitive support to the soloist in the limelight. The occasional flamboyant keyboard passages have plenty of crispness and character but are light enough to avoid dogmatically forcing the soloists to fight for attention.

Trio Sonatas – Op 2 HWV386-91; Op 5 HWV396-402

Academy of Ancient Music(Rachel Brown fl/rec Pavlo Beznosiuk, Rodolfo Richter vns Joseph Crouch vc) / Richard Egarr hpd

(Harmonia Mundi)

The Academy of Ancient Music’s project to record all of Handel’s works with opus numbers reaches its completion with this double-bill of 13 trio sonatas. Most are played by two violins (Pavlo Beznosiuk and Rodolfo Richter) and basso continuo (Joseph Crouch and Richard Egarr). The Op 2 set features two sonatas that specify slightly different scoring: flute in HWV386 and recorder in HWV389 (both played by Rachel Brown).

The interplay between the AAM is Baroque chamber-playing of the very highest order: sincerely conversational, emotive and finely nuanced. Egarr and Crouch are an outstanding continuo team, providing attentive yet uncluttered support to the two upper instruments. Brown and Beznosiuk play together with touching eloquence in the Largoof HWV386 and excel in the jaunty jig that concludes HWV389. Beznosiuk and Richter interweave to gorgeous effect in the Largo of HWV387. On a few occasions the slower music could perhaps have been trusted to play itself with a more literal rhythmical pulse, and sometimes things seem precious if compared to the best alternative recordings, but of course this may also be an unavoidable consequence of listening to an entire collection of works that were never designed by the composer to be sampled together in one long sitting.

Flute Sonatas

Barthold Kuijken fl Wieland Kuijken va da gamba Robert Kohnen hpd

(Accent)

In this recording of solo flute sonatas, Barthold Kuijken plays pieces unquestionably by Handel as well as others over which doubt concerning his authorship has been cast in varying degrees. Certainly not all the pieces here were conceived for transverse flute – there are earlier versions of HWV363b and 367b, for example, for oboe and treble recorder, respectively; but we can well imagine that in Handel’s day most, if not all, of these delightful sonatas were regarded among instrumentalists as more-or-less common property. Barthold Kuijken, with his eldest brother Wieland and Robert Kohnen, gives graceful and stylish performances. Kuijken is skilful in matters of ornamentation and is often adventurous, though invariably within the bounds of good taste. Dance movements are brisk and sprightly though he’s careful to preserve their poise, and phrases are crisply articulated. This is of especial benefit to movements such as the lively Vivace of the B minor Sonata (HWV367b) which can proceed rather aimlessly when too legato an approach is favoured; and the virtuosity of these players pays off in the Presto (Furioso) movement that follows. In short, this is a delightful disc which should please both Handelians and most lovers of Baroque chamber music.

Recorder Sonatas

Pamela Thorby rec Richard Egarr hpd/org

(Linn Records)

Pamela Thorby, a regular member of the Palladian Ensemble, demonstrates versatility and virtuosity beyond question and is imaginatively accompanied by Richard Egarr, who also contributes a sparkling account of the Harpsichord Suite in E major. The recording was made from facsimiles of the autograph manuscripts, and the performances are commensurately vivid and immediate. One feels constantly gripped by the music, as if every single note matters.

There’s no compulsive need for a cello on the basso continuo part, and on this occasion Thorby and Egarr manage perfectly well without one. Egarr uses a chamber organ on some of the sonatas, and although it’s not historically likely in Handel’s chamber sonatas, its musical effect is pleasing, and increases textural variety while removing the threat of monotony across 74 minutes of intense brilliance.

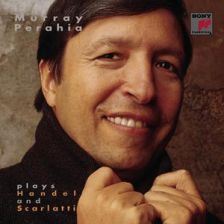

Keyboard Suites – in F; in D minor; in E. Chaconne in G

Murray Perahia pf

(Sony Classical)

In his projection of line, mass and colour, Perahia makes intelligent acknowledgement of the fact that none of this is piano music, but when it comes to communicating the forceful effects and the brilliance and readiness of finger for which these two great player-composers were renowned, inhibitions are thrown to the wind. Good! Nothing a pianist does in the Harmonious Blacksmith Variations in Handel’s E major Suite or the Air and Variations of the D minor Suite could surpass in vivacity and cumulative excitement what the expert harpsichordist commands, and you could say the same of Scarlatti’s D major Sonata, Kk29, but Perahia is extraordinarily successful in translating these with the daredevil ‘edge’ they must have. Faster and yet faster! In the Handel (more than in the Scarlatti) his velocity may strike you as overdone but one can see the sense of it. It’s quite big playing throughout, yet not inflated. Admirable is the way the piano is addressed, with the keys touched rather than struck, and a sense conveyed that the music is coming to us through the tips of the fingers rather than the hammers of the instrument. While producing streams of beautifully moulded and inflected sound, Perahia is a wizard at making you forget the percussive nature of the apparatus. There are movements in the Handel where the musical qualities are dependent on instrumental sound, or contrasts of sound, which the piano just can’t convincingly imitate. And in some of the Scarlatti one might have reservations about Perahia’s tendency to idealise, to soften outlines and to make the bite less incisive.

more to Gramophone.com…

Share it people